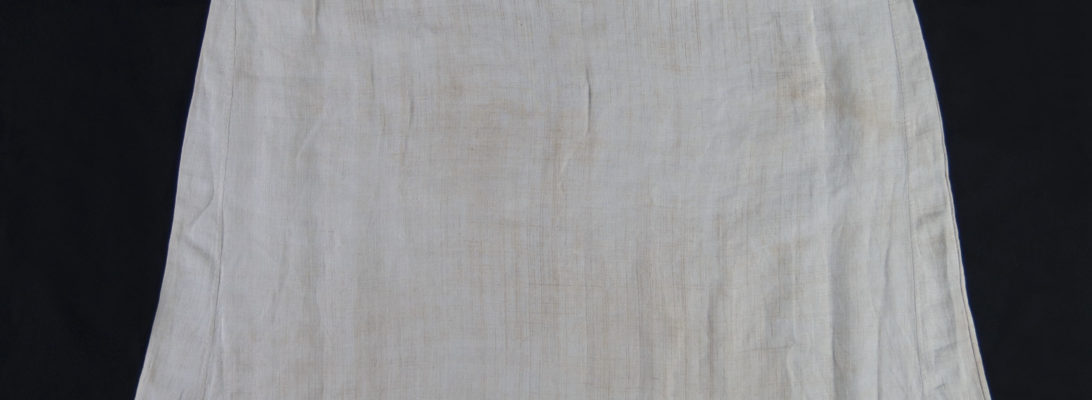

Shift, c. 1780–1805

Linen with cotton patches

Source unknown

1997-011-001

A shift, a common piece of women’s underclothing in the eighteenth-century that was shaped like a long t-shirt and worn next to the skin to protect outer clothing from sweat and body oils, is now a rare, and thus special, artifact to have in the collection. Few exist today because they were not considered important keepsakes in their time, but instead everyday clothing to be worn until they deteriorated beyond use. The shift in the Carpenter Museum’s collection was patched many times by its owner in an effort to prolong its life: at both shoulders, on one sleeve, and in three areas on the front of the garment.  Patching was preferable to making a new shift, which would have required much labor—from growing and processing the flax to spinning the thread to weaving the linen. Finally, a woman would have cut the fabric and sewn the garment together by hand. The owner of this shift cross-stitched her initials, HR, on the front directly below the neckline.

Patching was preferable to making a new shift, which would have required much labor—from growing and processing the flax to spinning the thread to weaving the linen. Finally, a woman would have cut the fabric and sewn the garment together by hand. The owner of this shift cross-stitched her initials, HR, on the front directly below the neckline.  She still has not been identified, however, as Rehoboth vital records list many Reeds, Rounds, Richmonds, and Robinsons at the end of the eighteenth-century and among those many Hannahs, Huldahs, Hopestills, Hepzibeths, and Hesthers. The only other clue we have is the shift owner’s body type. The dimensions of the garment reveal that she was approximately 5 feet 2 inches tall and rather stoutly built.

She still has not been identified, however, as Rehoboth vital records list many Reeds, Rounds, Richmonds, and Robinsons at the end of the eighteenth-century and among those many Hannahs, Huldahs, Hopestills, Hepzibeths, and Hesthers. The only other clue we have is the shift owner’s body type. The dimensions of the garment reveal that she was approximately 5 feet 2 inches tall and rather stoutly built.